Note: This blog is about the first episode of Crisis in Care. It’s on BBC iPlayer now and will be available for 11 months.

Intimate Access

The word ‘access’ is an important one in the documentary lexicon. The difference between a pie-in-the sky idea for a film about, let’s say Facebook’s hate speech monitoring team and a pitch that will get commissioners excited is ‘access’. Organisation X allowing filmmakers Y in to film them. One of the special aspects of Crisis in Care was the ‘access’ granted by Somerset County Council – because council’s don’t tend to open their doors to filmmakers – much less those struggling with their finances to the extent that Somerset were. As privileged as this access could be said to be, the really privileged access in these films were the families giving and receiving care; letting us in to film some of the most private aspects of their lives.

It didn’t take long to realise I couldn’t film people with the usual ‘barriers’ we often hear talked about by journalists and filmmakers. I’m not sure what I was ‘supposed’ to do or how to feel but I cared deeply about everyone I filmed. This led to real relationships with them, not fleeting ‘film and go’ ones. Talking, joking, getting to know each other with the camera turned off made us far more comfortable with each other. It made me realise that if filming is given the space to become a sort of social occasion, where you can chat, have a moan and a laugh together then it means filming is nicer for them and usually less rushed for you which translates into more time to capture a situation authentically.

There was no pretence in that and it wasn’t a ‘tactic’. My working theory is that most humans can smell insincerity a mile off. If you really care then it really shows and, from my albeit limited experience, it has the unintended but fortunate consequence of better filmed material – and by better I mean more natural, truthful, more reflective of the reality when the camera is not there. I think everyone we filmed with knew that this wasn’t just a film – we all really wanted to make something that made an impact. We were truthful about that and it must have resonated with people who, despite being in difficult personal situations, allowed us to film what adult social care looks like to them on a day-to-day basis.

Filming Night Care

The most obvious example of this was filming the night time care with David and Martine. It was private and difficult thing to let us film, so Angie decided I should go alone to keep crew intrusion to a minimum. It was by far the hardest thing I’ve ever filmed. I knew that things weren’t easy for David and Martine but to sit and witness it – to feel a thin slice of what goes on for them every single night was sobering. Technically speaking it wasn’t easy either. It was dark and my camera was at it’s low light limit – I was already pushing the C300 to the upper end of it’s ISO but any more and the picture would have capitulated into a fizzy, fuzzy mess (the result of high ISO settings).

David and Martine were exhausted from a long day and I’d already been there for hours by the time the sleep / wake / move / sleep / wake / medicate cycle started. It was intimate, private and for Martine, very painful. When the lights went off and they went to ‘sleep’ and night care started, the room suddenly closed in on me. I felt every breath and move and sound I made, feeling less like a fly on the wall and more like a bull in a china shop. If David and Martine were perturbed by my presence they didn’t let on, but I couldn’t help but put myself in their shoes, imagining a man with a camera present in the room moments after waking up, watching bleary-eyed care being given and received. I tried not to move around too much, shooting most of it from one spot in the corner of the room, sitting, standing and zooming for variety and editing options. When they went to sleep again I’d carefully and quietly adjust position to get another angle. Of course, my job is to film but my priority was their wellbeing. I didn’t want to contribute to their already-extensive tiredness.

Other filmmakers have since explained I shouldn’t self-restrict so much – afterall, we have been invited in, with full consent and to tell a story and we have to get the best angle to depict what goes on faithfully. I get it. That’s where that professional distance might be useful. But – I would suggest that had those barriers been up from the outset, we never would have got to the level of friendship and trust that I feel it took for us to be invited to film the night care. I’m sure every filmmaker has a different approach and maybe others would ask for the lights to be kept on or feel they could move around the room with liberty. Whether it’s inexperience or oversensitivity as a person, my instinct was to try to fade into the background, not to move much and deal with the low-light in-camera instead of asking to turn on a lamp. I felt it was intimate so I tried to handle it with as much respect as I could and to me that translated to minimising my impact.

I don’t know what the ‘right’ way to do it was but that’s how I did it. I just hope it was enough to give audiences an insight what the reality of putting financial decisions ahead of people looks like. Like David says, we do it for the people we love. But that love is being relied on to prop up an underfunded and under-though-through system. As it stands, some family members aren’t just being asked to plug a few of the gaps that even an excellent care system likely couldn’t entirely fill – some are forced to provide high level, technical care to the detriment of their own health, wellbeing and employment as a direct result of financial decisions made by government which filter down to councils. That was the case for David and Martine and it will be the case for many families around the country. Instead of people just talking about the strain on them and the upshot of cuts, the night care was intended to show some of what the more extensive care provided by family members actually looks like in practice.

Filming Rachel and Barbara at home

The day after filming the night care with David and Martine I spent the day with Rachel and her mum Barbara. Fortunately, I’ve never experienced dementia up close but within a single day of filming, I was exhausted by the difficult behaviour, outbursts and repetition that it presents. Through the camera, I tried to capture the feeling I had, that Rachel was stuck in a constant, draining loop. I held my shots for longer than usual, letting the repetition play out calmly, slowly, in frame, no quick pans or rushed cutaways to break up the interaction playing out between Rachel and Barbara. I was trying to get a slow pace and repetition into the footage itself so that Angie and the editor would feel it, so that eventually the audience might feel it too.

I think one of the shots or sequence I captured most successfully across the entire production was Rachel helping Barbara to go for a shower. It started in the kitchen and I filmed it on the long end of the 70-200mm lens. I wanted to convey a claustrophobia that I felt came with living with somebody with dementia so kept it very close. Practically speaking, I knew that a shower was planned at some point so I had to frame shoulder height and above for privacy. I like the closeness of the shots but also a strange distance that comes from shooting through the doorway, just edging the frame. What happens next, Barbara’s outburst, and then soiling in the bathroom must be typical behaviour for Rachel to deal with but it might be surprising to viewers – it certainly was to me.

I feel we captured something intimate and private but essential for giving an honest insight into the life of somebody caring for a mother with severe dementia. I was glad that I managed to do it in closeup and as a (pretty much) continuous shot, no camera readjustment or fiddles, just unfiltered interaction that grounds us in the present. I think there’s a cut in the edit purely to move the scene along, but no cutaways are used. It resonates with me because I feel there’s a presentness and immediacy to it. I was shattered after the night filming the day before, but more than any other time on the shoot, it felt like I was on a roll, shooting with fluency, suspended in a trance by Barbara and Rachel’s interactions and glued to my camera as a result. It sounds silly but more than any other time on the project, it felt like the camera was a limb, part of me. Maybe the pros always feel that good – that would be nice, wouldn’t it?

Drained

I left the house with a drive back to Surrey through the December night. It was the last shoot before we took a break over Christmas. I was tired but I was confident that the last 2 filming days had given us some really key moments for the film. A short while into the drive I pulled over and called Angie, feeling wrung out after the last few days. I like to think of myself as having a good engine, late night shooting and early starts has never been a problem. But that night I was drained – more drained than I felt even a 4 a.m finish the night before should warrant.

It must have been the longest I’d ever spoken continuously and uninterrupted to Angie. No, at Angie. It was certainly the most emotional I’d been and the first time I felt it more important to talk than to be guarded. To date, I had this idea in my head that I was being assessed, judged on my competency as a filmmaker, if I the chops to have a career, at all times. Over the course of the project, I wasn’t just obsessing about the pictures and sound but the things I talked about and how I came across outside of shooting hours. That was exhausting. It’s clear now that I put far too much pressure on myself. I want to talk about this feeling in more detail because I wonder if it’s common, experienced by others who feel they’ve been handed an opportunity so great that everything they do and say is make or break. Or maybe it’s just me and my own insecurities. I’ll leave it there for now but will go into more detail in my next post after episode 2 goes out.

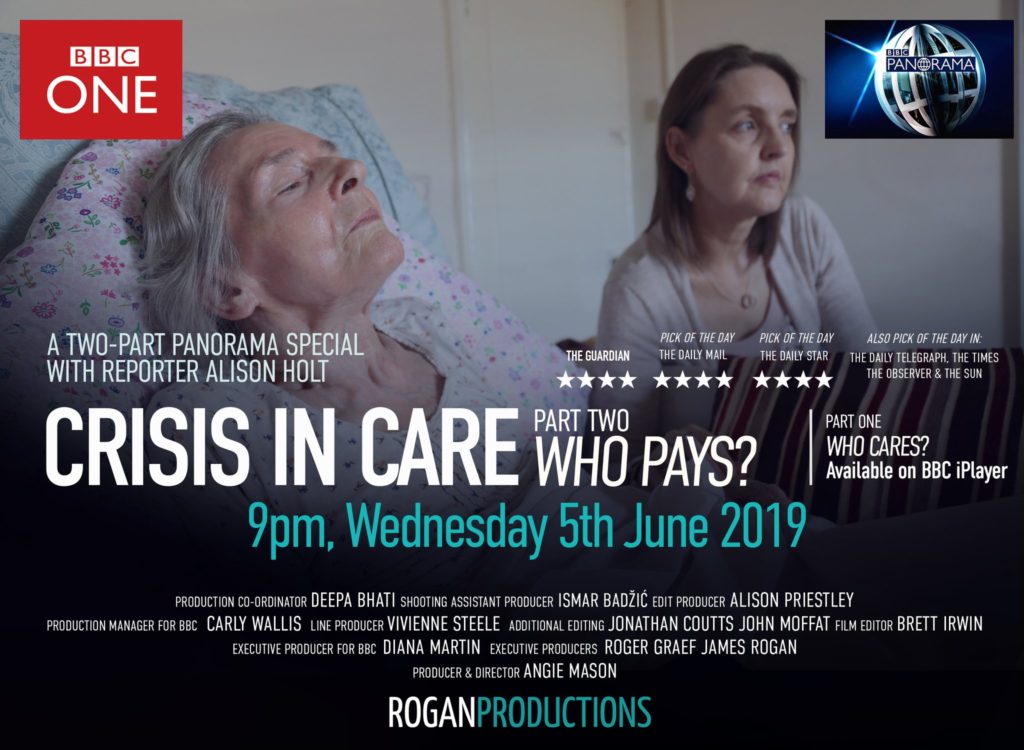

Crisis in Care: Who Cares? is on BBC iPlayer now (available for 11 months)

Crisis in Care: Who Pays? BBC One at 9pm on Wednesday 5th June

I work with Dementia everyday and I am really looking forwards to part two tomorrow. I feel you have given an insight into our world which is not given as a rule, but, should be. There is so much hype about it now and Dementia is the ‘buzz’ word of the moment, but, do people really understand what it is all about? No of course they don’t and neither can they be expected to as the only way to truly know how it is, is of course to live with it. The next episode I believe is about residential care and the company I work for is featured. If this episode is as good as the first, I for one won’t be disappointed and I thank you for doing this. The more people know about what living with Dementia is really like the better as it is not going to go away.